The December 2021 issue of Ripperologist: The Journal of Jack the Ripper, East End and Victorian Studies contains an interview I gave to How Brown, the proprietor of the website CarrieBrown.net, and Mr. Brown has graciously agreed to allow me to reprint the article on my blog.

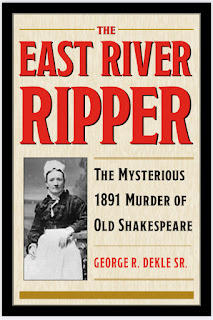

THE

EAST RIVER RIPPER

THE

MYSTERIOUS 1891 MURDER OF OLD SHAKESPEARE

By HOWARD

BROWN

Recently

released by the Kent State University Press was The East River Ripper: The

Mysterious 1891 Murder of Old Shakespeare by author George R. Dekle, the

first full-length book on the murder of Carrie Brown. Her death has seen much

discussion over the years as to whether it was the work of the Whitechapel

murderer.

“This book

will, for the first time, give an accurate history of the East River Ripper

case. It will not give an infallible account of what really happened. No

history can do that. All history can do is reconstruct an account of what

probably happened. The more numerous and reliable the sources, the more

meticulous the historian, the more accurate the history can be, and no effort

has been spared in making this history as true to what really happened as humanly

possible.”- George R. Dekle, from his Introduction.

Professor Dekle, not only the first crime scholar to have written a full-length book about the 1891 murder of Carrie Brown, the trial of Amir Ben Ali, and the aftermath to this Gilded Age mystery, is perhaps the best person who might have written a book about the case. His legal background separates him from the pack by the very fact that he covers Ali’s trial, and does considerable damage to the long-held belief that Ali was framed by the NYPD, a belief which came about almost immediately after the June/July 1891 trial.

Professor

Dekle provides alternative theories as to who committed the murder, and leaves

the casual reader and Brownian researcher the option of choosing which of his

alternatives is closest to the truth as to whodunit.

The book

doesn’t shut doors, but rather opens them in terms of encouraging further

research into the East River Hotel murder.

The East

River Ripper is a must-have book for aficionados of Gilded Age

American crime and true-crime devotees of every stripe.

u

FIVE

QUESTIONS WITH GEORGE R. DEKLE

1: When did you begin

your research into the Carrie Brown murder and Ali trial? How much time, from

the beginning of the research until the completion, did it take for you to

complete the work?

Toward the

end of 2018 as I was finishing up my last book, Six Capsules: The Gilded Age

Murder of Helen Potts, I decided to write a professional biography of the

lead prosecutor in that case, Francis L. Wellman. The format would be to give a

chronological account of his murder trials, devoting a chapter to each one. I

had followed this path once before, when I wrote Abraham Lincoln’s Most Famous

Case: The Almanac Trial. Upon finishing The Almanac Trial, I then

wrote Prairie Defender: The Murder Trials of Abraham Lincoln.

I started on my project exactly as I did

on Prairie Defender. I amassed all the information I could on every

murder case that Wellman tried, and then began writing the book. When I hit the

second chapter, I said to myself, “This case deserves a book unto itself,” but

I forged ahead. When I got to the fifth chapter, I said, “It’s impossible. This

case has to be a book unto itself.” Then I really dug into the research on the

Carrie Brown case and uncovered a wealth of information that confirmed my

opinion. I set aside the professional biography of Wellman and wrote The

East River Ripper instead.

I worked on the book from October of 2018 until January of 2020, at which time I had a completed manuscript. KSU Press accepted it for publication, and for the next six months I worked on responding to the critiques of the peer reviewers, rewriting to address the critiques, correcting mistakes found by the copyeditor, reviewing proof pages, and indexing.

2: What was

the most interesting part during your research? Scouring the trial transcripts?

Reviewing first hand accounts, or something else?

The most

interesting moments during my research were the times that I found things which

had certainly been overlooked by the lawyers trying the case and apparently

overlooked by later writers on the case. As I tried to point out in the book,

the prosecution didn’t put on nearly as strong a case as they could have, and

the defense missed gaping holes in the prosecution case that they might very

well have exploited to achieve an acquittal.

3: When you

give the reader three alternatives to a solution in this case, was it entirely

for the reader or are you not entirely convinced an answer or solution is

etched in stone yourself.... or both?

I talk about some of the

principles of evidentiary analysis when I give the three case theories. One

really important principle that I had to learn the hard way is: “Don’t get

tunnel vision.” Don’t latch onto a theory and defend it at all costs no matter

what new evidence turns up. Byrnes didn’t do himself any favors by latching

onto the “Frenchy No. 2” theory and not giving up on it until he had

established that “Frenchy No. 2” had an ironclad alibi. Then he continued to

let the public think that he was looking for Frenchy No. 2 and wound up with

egg on the face when he arrested Ben Ali.

You look at the evidence and devise theories which explain as much of the known evidence as possible. Then you test those theories to see if they hold up under scrutiny. The three theories I advance in the book were what I believed to be the three most plausible theories. Any one of them has a claim to being true, but which is most likely true? In devising the three theories, I looked at all the evidence without analyzing its weight. In choosing among the three theories, I weighed the evidence, accepting what I felt was more believable and rejecting what I felt was less believable. The weighing of evidence is a more subjective process than simply looking to find the existence of evidence.

Could I be wrong about whether

Ben Ali committed the murder? Certainly I could. As Oliver Cromwell wrote to

the Church of Scotland, “I beseech you, in the bowels of Christ, consider that

you might be mistaken.” This dictum gave rise to the scientific principle known

as Cromwell’s Rule: “Never assign a probability of 1 or 0 to any proposition.”

Statistician David Lindley coined the term, and he illustrated it by saying

that you should “leave a little probability for the moon being made of green

cheese; it can be as small as 1 in a million, but have it there since otherwise

an army of astronauts returning with samples of the said cheese will leave you

unmoved.”

Somewhere out there someone may find a piece of evidence that proves beyond peradventure that Ben Ali was innocent. I think it’s unlikely, but it could happen. What I haven’t seen is any evidence whatsoever that the police, the expert witnesses, and/or the prosecutors colluded together to frame an innocent man. The only “evidence” of a frame job that I found was the unsubstantiated allegations in the press that Ben Ali was “railroaded” and Charles Russell’s statement in his highly inaccurate magazine article that there was “something strange” about the blood evidence. These allegations got repeated over time until the acorns of allegation grew into the oak forest of certainty.

Sometimes people can get trapped in a web of circumstances indicating guilt that they cannot extricate themselves from, and that may well have occurred in Ben Ali’s case. I handled a murder case once where an idiot kept doing stupid things that made him look guilty. I felt sure I could have convicted him at trial, but I was just as sure that he was innocent. We didn’t arrest him, and a year later we were able to arrest the man who actually did commit the murder. When I was a defense attorney I had a client who accidentally killed his girlfriend and then staged the scene to make it look like a rape-murder and throw suspicion on someone else. He took a manslaughter and turned it into a first degree murder and wound up getting sentenced to life instead of 15 years for manslaughter.

You get more false convictions from bad luck and bad judgment than from bad police officers.

4: If you

were a defense lawyer for Ali. what would have been (at least) one strategy you

would have undertaken that the trio didn’t, or one that you would have handled

better?

The

prosecution went to trial unprepared. Francis Wellman delivered what seemed

like a good opening statement, but it had gaping holes in it where he said things

that he could not prove. The defense did not take advantage of these failures

of proof. They actually papered over one of them. The prosecution wound up

putting on a better case than what they said in opening (but not nearly as good

a case as they could have), and the defense responded to that case with experts

who could easily have been turned to support the testimony of the prosecution

experts. The prosecution fumbled badly in their handling of the defense

experts. Instead of using the defense experts to bolster their own experts,

they attacked the defense experts.

The way to defend Ben Ali was to defend against Wellman’s opening statement, not against the evidence presented at trial. In taking that approach, the defense could ignore most of the damning new evidence that hadn’t been mentioned in opening statement and cross-examine the prosecution experts to have them underline all the things that Wellman had said but failed to prove. I would have worked hard to keep Ben Ali off the witness stand. He never looked more guilty than when he was denying his guilt. Wellman butchered him on cross-examination, and that may well have been the turning point of the trial. More times than I can remember I have seen a defendant who was sailing toward a not guilty verdict take the witness stand and snatch defeat from the jaws of victory by lying like a cheap clock. Usually it was a client I couldn’t talk out of testifying.

It might be hubris on my part, but I think I could have gotten Ben Ali acquitted by following the strategy outlined above. I don’t mean by my remarks to disparage the efforts of either side. They both worked hard, and both sides did enough to win the case before the right jury. The problem was that the only truly experienced criminal trial lawyer among the six lawyers was De Lancey Nicoll, and he was only a mediocre trial advocate. The other lawyers were talented, and they occasionally showed flashes of brilliance, but they all needed some seasoning in the trial of murder cases. Wellman was a quick study, and he showed vast improvement in his next case, the Carlyle Harris case chronicled in Six Capsules.

5: Our opinion of George Damon, the

Cranford, N.J. man who came forward with the key to room 31 approximately a

decade after Ali had been in various institutions, is probably the same. What

might differ is what reason he had for coming forward. Do you believe this

reason was self-serving or altruistic?

If George

Damon was telling the truth, what else must be true? (1) It must be true that

the police had no hope of ever finding out the true identity of “C. Knicklo.”

Damon, the only man who knew it, was concealing it. (2) It must be true that

the police had no hope of ever finding the key to the death room. Damon was

concealing it. (3) It must be true that George Damon valued his personal

convenience over the life of an innocent man. Ben Ali stood in danger of death

in the electric chair and only Damon could save him. (4) It must be true that

George Damon didn’t give a damn about the proper administration of justice.

Conclusion: George Damon was the real villain of the tragedy of Ben Ali’s false

conviction.

The

unspoken theme of George Damon’s testimony, whether true or false, is “I’m a

dirtbag.” When someone says, “I’m the kind of guy who will let an innocent man

die in the electric chair,” he’s not the kind of guy I’m going to rely on to

tell the truth. And he’s not the kind of guy I’m going to expect to act from

pure motives. I’ve had quite a bit of experience with post-conviction

“exculpatory” witnesses, most of them as a defense attorney. The usual scenario

was that the witness came to me and said, “What do I have to say to get the

defendant’s conviction overturned?” None of these witnesses were motivated by

altruism. I suggested one selfish motive for Damon to fabricate the story of

Frank the Disappearing Dane in the book. There may have been others for which

we have no evidence.

u

HOWARD

BROWN is the owner of CarrieBrown.Net, the foremost online archive and

discussion site on the Carrie Brown murder.